| Go to the table of contents | —by Fiora Gandolfi | Lire cette page en français |

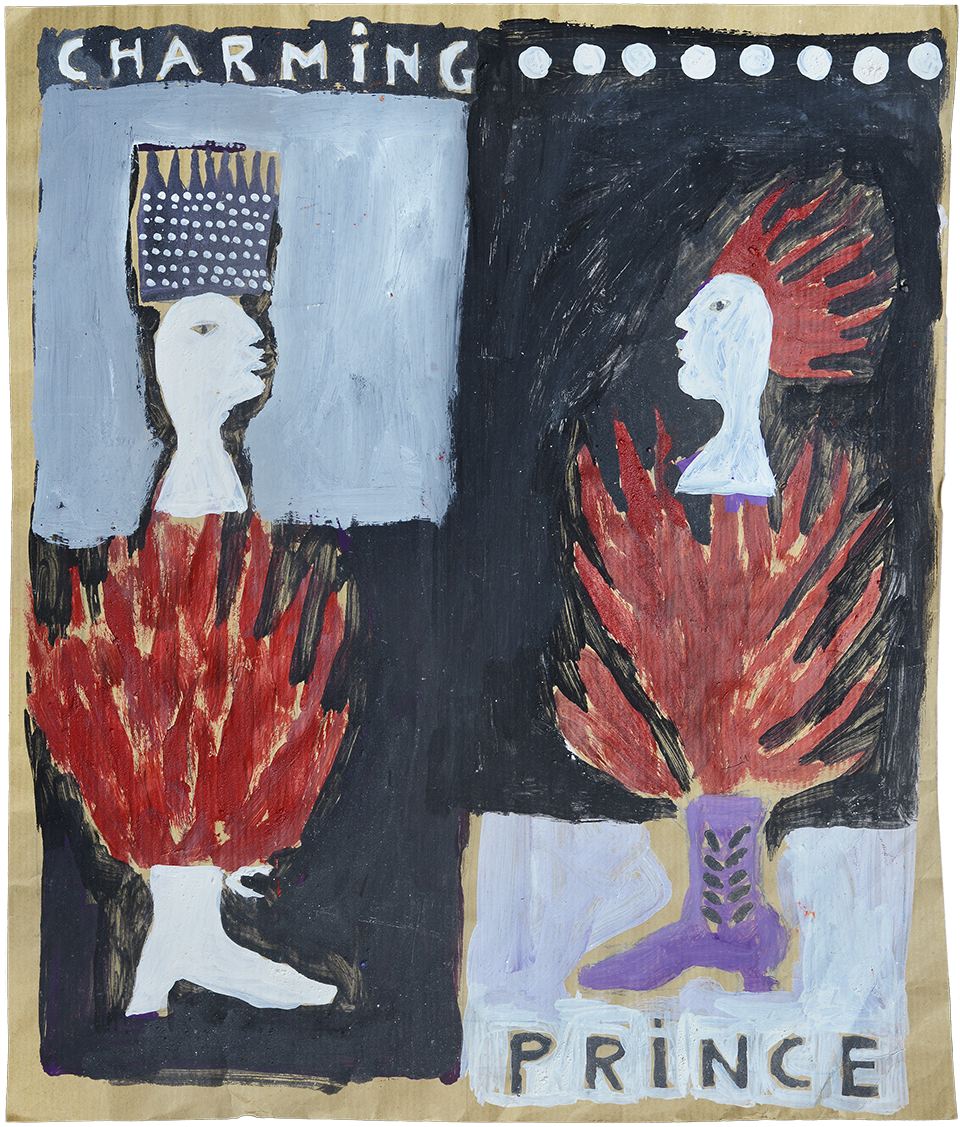

—painting courtesy Cyril Skinazy

Venice is the city of seduction and love, because it is a city with many faces, unstable, always and yet never the way it goes as in love.

But to find love in Venice, it’s better to bring it along in your luggage. Having your own supply of love is essential. Because there’s no youngsters, no disco, no sex shops, no prostitution that have found their way on to dry land, in Mestre or in Terraglio, the road planted with trees by Napoleon that leads to Treviso. Black goddesses are found there, a symbol of abundance and fertility that would have pleased Fellini, fairy white creatures of Eastern Europe, as huge as Giacometti’s sculptures.

There’s an unassuming and very private home in Venice in front of Calle dei Preti in the Santa Maria Formosa quarter.

On the top floor, women from the middle east close the curtains when a minister arrives in this city dotted with sumptuous palaces inhabited by the rich and old retirees.

A deep dichotomy cuts Venice in two: it’s a city filled with what is virtual and physical, a city of passion and death; many intellectual’s bodies have been repatriated in secret after they committed suicide. It is the city with palaces decorated like lace, built on legions of invisible slaves, tree trunks chained together supporting buildings seem to float on the lagoon waters.

In Venice the virtual city, which everyone dreams about, lives side-by-side the everyday city where everything is different. There are two cities that overlap for lovers who have succumbed to the charms of the Serenissima and fearlessly wander about the dark maze of narrow streets. There’s no Minotaur hiding there, no Ariane awaits the visitor there, no motor vehicles will bother walking lovers. The streets are covered with water and lions fly, as said Jean Cocteau.

In Venice you will also come across a gondolier who is also a specialist of China, Gabriele Foccardi. Pushing an oar in the waters of the Grand Canal costs less than dipping his brush in ink while drawing ideograms. Couples come to this city to play out a scene in a play: the story of their love. They let themselves go, tranquilly, as is they’re looking at a web site on their computer. Where Venice is located has the advantage of completely enveloping you, calling not only on the sense of vision but the other senses combined. Lovers walk hand in hand, in a surreal landscape of palaces reflected in the water, reflections which break up and come back together as gondolas go by. In this endless game, the city penetrates one’s body by osmosis through every last pore.

The sounds of Venice send shivers down one’s back: the gentle lapping sounds of water on gondolas moored on the Grand Canal, the cry of suffering moored vaporetti, echoed in the music of Luigi Nono. One’s nostrils are awoken by smells which have long since disappeared from big cities: a white kind of smell of a mystical bread oven. The smell of the fog, the smell of seaweed. The sense of touch, a lesser sense scorned as is the sense of smell, comes back to the forefront in the subtle sensibility of Venice. One’s feet listen to the bumps in the sidewalks. Certain steps make you feel the moisture of the grass, others the moss growing between the cobblestones. Other footsteps land harder on the old soil from the belly of a volcano. There are footsteps that teach nothing, walking on smooth new pavement where solidified lava would have seemed to belong too much to the past (it’s sold to American and Japanese cities, etc…) Venice is the only city where the sound of one’s own footsteps can be heard along with the vibrations of one’s own body.

—painting courtesy Cyril Skinazy

Love and Death: top secret. In silence, thousands of foreigners have come to commit suicide in the hotel rooms of Venice. This phenomenon has been the subject of a doctoral thesis at the University of Padova. The scene is always the same. The bottle of pills on the night table next to a book by Thomas Mann… a complicit silence hides all these corpses: the victims’ relatives, hotels, newspapers, even the city government say as little as they can about such events. Death is an indecent secret, of no interest as concerns the myth of a city that chose to name itself “Serene”. In each body there is excess of absolute truth that troubles the frivolous elegance of the city of love.

Lovers come to Venice to bring home a series of photos or videos constituting proof that their journey of love was true and real.

Japanese who get married in their own country enjoy filming a fake wedding ceremony in a friendly salon of the Lido hotel decorated to look like the ca’Farsetti, Venice’s city hall. A fake mayor who doesn’t look anything like Franco Costa let alone Massimo Cacciari gives the wedding rings and says, “vi dichiaro marito and moglie” (I now pronounce you husband and wife). The actor who plays the mayor, usually a nightclub bouncer, charges 500,000 lire ($300) for his performance. Generally he’s a handsome Italian who looks like Cornetto Algida and is impressive in the video souvenir with his jacket crossed by the municipal white red, green and gold ribbons. The Japanese film the ritual of the rings and the cake, the gondola ride with the bride lost in a nylon mesh cotton candy wedding gown.

Once they’ve arrived in the Serenissima, couples from the rest of Italy play roles in a performance of the great actors: they show off with expensive Borsalino cigars and drink cappuccino at Caffè Florian. They shoot videos while posing for photos. Click: Backdrop, St. Mark’s Square. In the foreground are pigeons landing on the heads and shoulders of lovers who have no idea that leprosy mutilates their scabrous red legs.

Click: On the bottom steps on the Rialto Bridge, after walking up. The tired lovers lean on the railing for their photo. They don’t notice that the rough Istrian stone, cherished for centuries in this spot has become smooth and warm like the inside of a woman’s thigh.

Click: On Ponte della Paglia, lovers are photographed intertwined like snakes and salamanders. “Ah! The Bridge of Sighs…” The tour guide explains that that the sighs came from despairing prisoners being taken off to prison. They’d rather believe that the sighs concern lovers in gondolas. The truth is what gives pleasure.

Yet in Venice the precious gift of the exchange of bodies was quite fashionable. Courtesans such as those painted by Carpaccio were mistresses of the charm of sex and culture. They were Italian geishas. They wrote, sang, composed music and knew Latin and Greek. On a trip to Venice King Henry III did not pass up on the opportunity to enjoy the charms of Veronica Franco, one of the most famous courtesans in history. The first woman who ever dared to go to university was born in Venice. Elena Lucrezia Cornaro, a noble born in 1646, was the first woman to obtain a university doctorate.

Venice was also known in the eighteenth century for its “casini”, tiny secret spaces, elegant little apartments hidden in the dark streets around Piazza San Marco. They was about a hundred of them, featuring emergency exits allowing players and lovers to flee. Servants were not allowed to see guests’ faces and served them chocolate, tea and cakes through a small opening between the kitchen and the salon. A dozen of those charming casini belonged to highly-respected women of the aristocracy, like the casino Venier, now the headquarters of the French Alliance on Ponte Baretteri.

From the point of view of love the eighteenth century was far more evolved than our era in that noble wives had the right to keep tiny “rabbit hutch” side apartment and their husbands and friends pretended they knew nothing about it. A popular citation back then was the famous phrase attributed to Lesbia of Catullus, the Roman poet born in Sirmione in the Venice region: “Let us live and love us no matter how much old folks might grumble at us.”

—by Fiora Gandolfi